Bear Prince, Slumberland, Many Hats

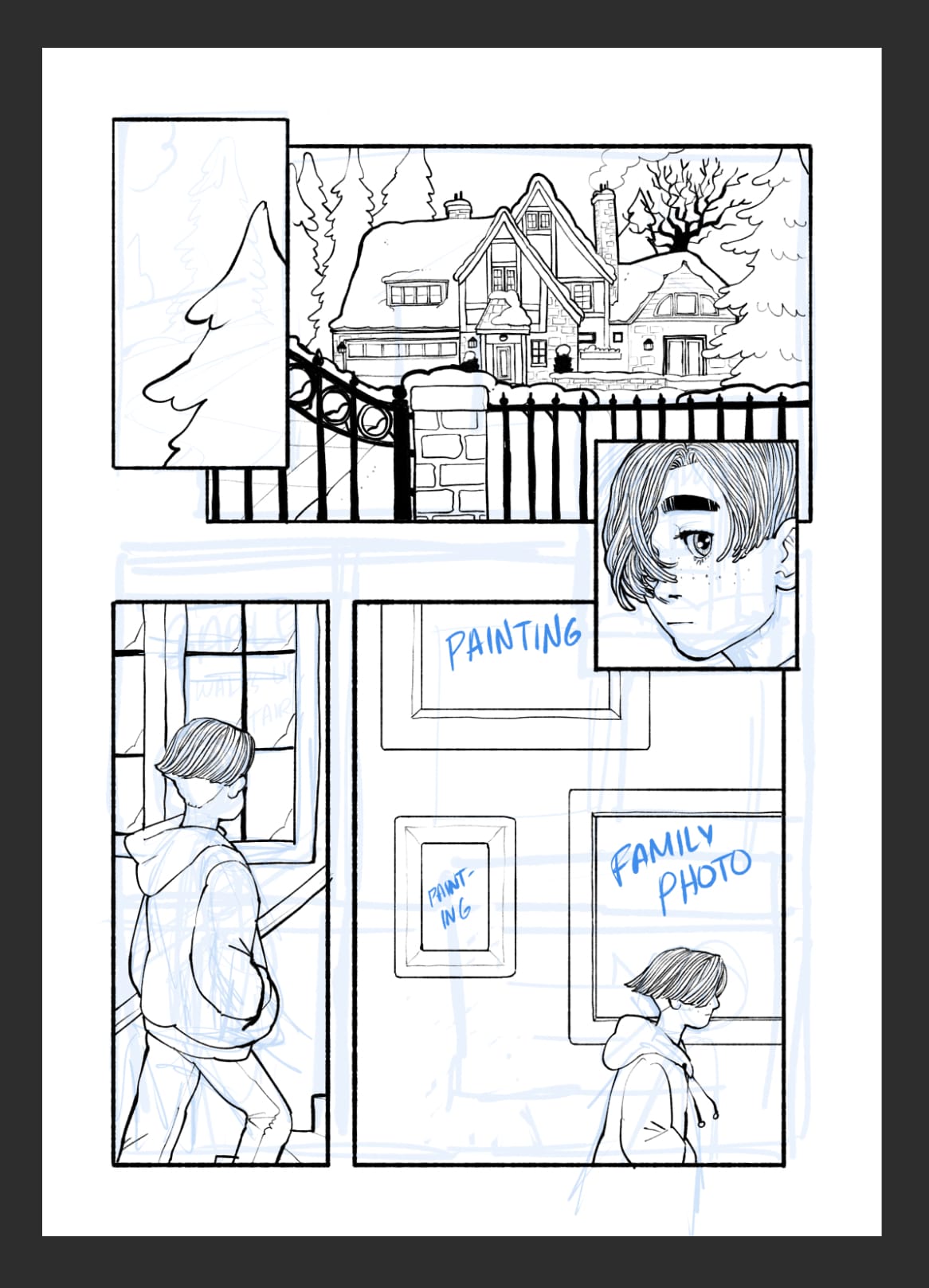

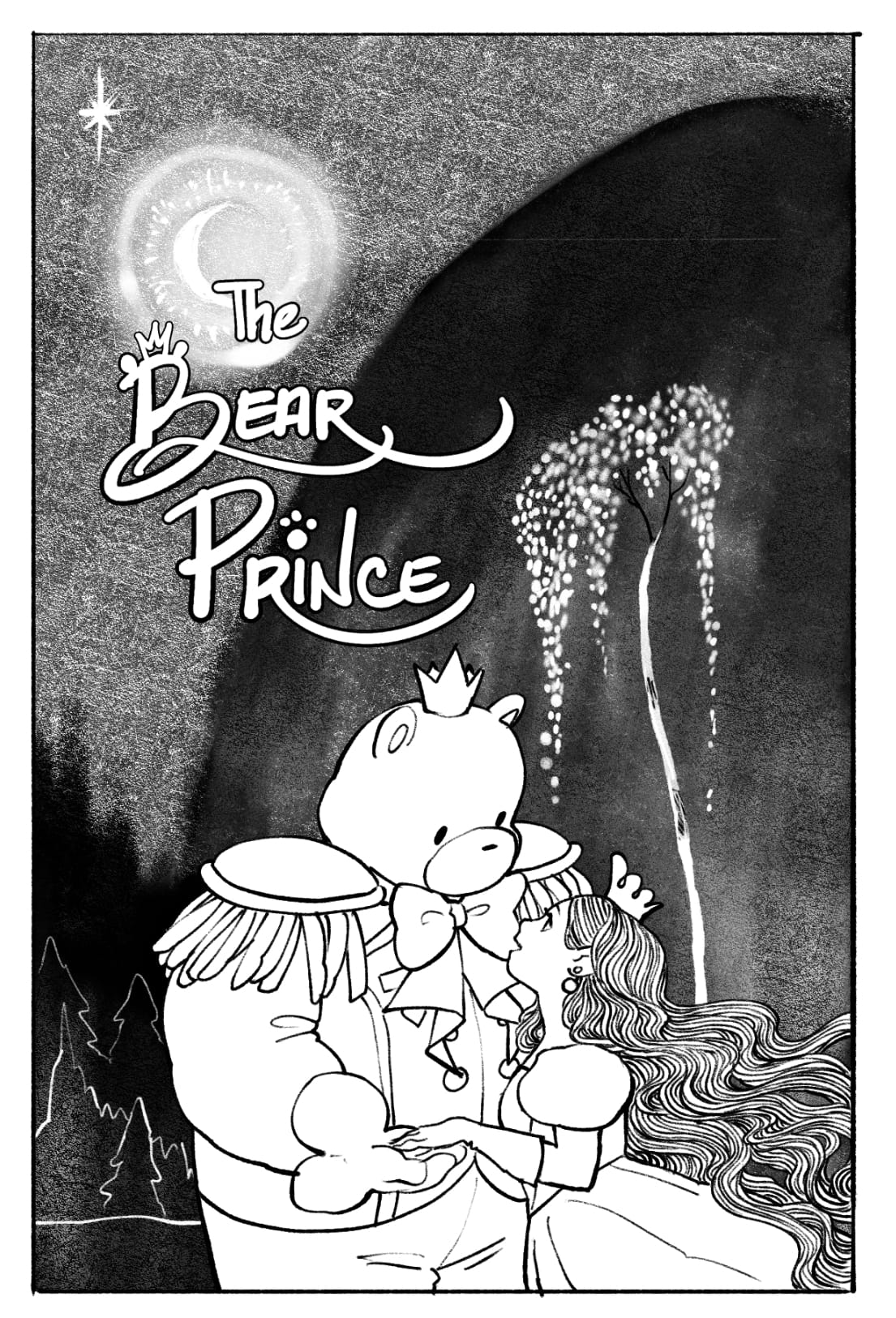

This week, I am deep in the comics trenches and hopefully making progress with pages for Angelica and the Bear Prince. I keep accidentally making wild amounts of work for myself by doing things like, for instance, writing segments that take place in rooms with a lot of meaningful picture frames. Or I'll include pages where the main character scrolls through social media galleries, and I'll have to draw all those posts, too. I don't know why I did this. I'm always doing too much, and there's no way around this sort of work but to just do it, one bit at a time.

Somewhere in my professional and creative development, I'd gotten it in my head that place-setting is as important to a story as costuming and character design. Heck, place-setting probably is, to a great extent, also character design. I have no background in either of these things. My formal technical arts education went as far as "look at thing, paint thing," while my friends who work in illustration or animation have this sense that the design of a visual environment helps situate a viewer in the right headspace for a story. Are the corners soft or sharp? Are the lines curved or straight? Is there a lot of wood in the rooms? Is it dusty or clean? Is it cluttered or neat? Is the palette warm or cool? All these things help make a story space, and I'm figuring out how to navigate all of it without, you know, hurting my wrists or shoving all my deadlines way, way into the future (apologies to my very patient editors).

I love intergenerational stories. My books so far center the experiences of protagonists within a middle grade or young adult age range, but I love exploring parent-child relationships. In The Magic Fish, I spent a lot of time fleshing out the visual landscape of each character's visual imagination to construct the little fairy tale universes that bloom when they each tell a story. Bear Prince is going to have a little bit of that, too, though the visual references are slightly more streamlined. I'm always kind of a little bit dealing with the past.

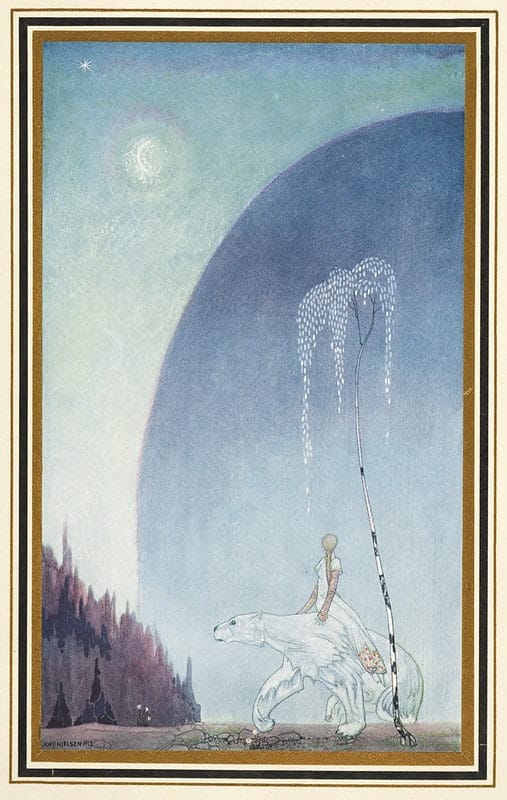

One in-universe poster I designed for the book is based on a Kay Nielsen illustration for a story that is my own book's namesake, East of the Sun and West of the Moon: Old Tales from the North, which is freely available for you to read as it is in the public domain.

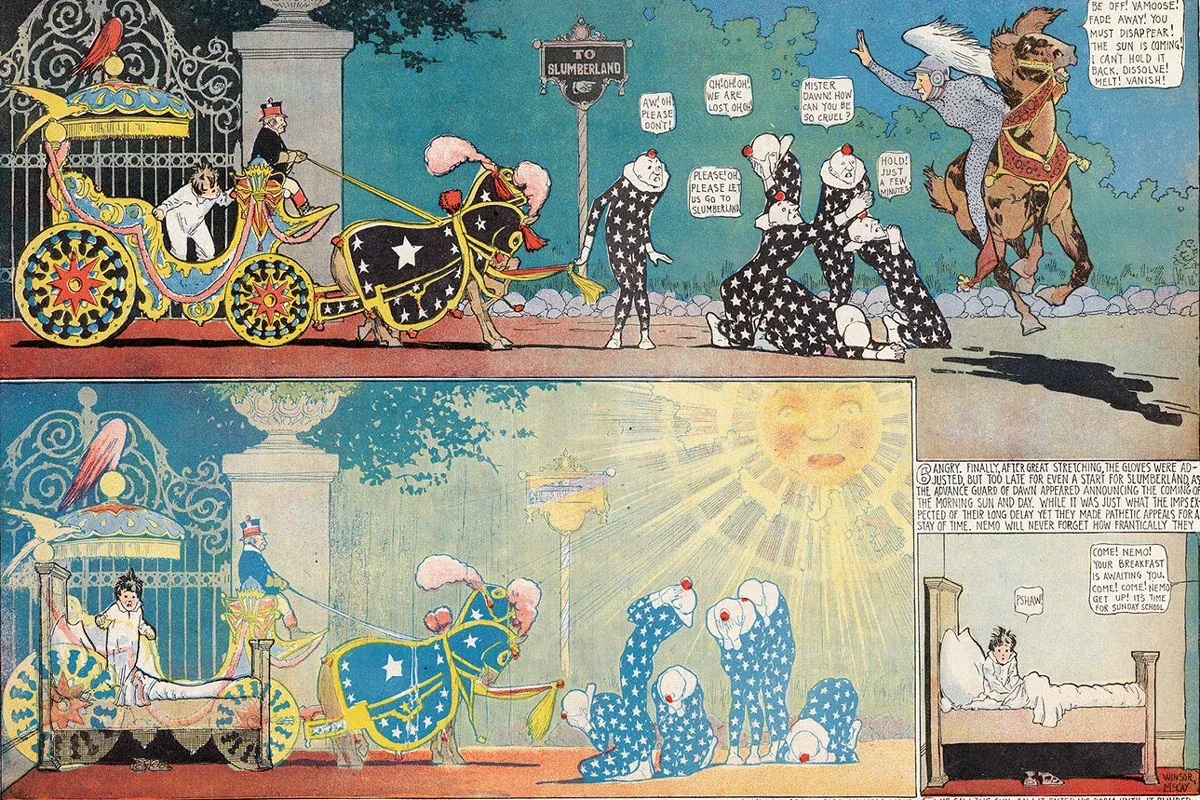

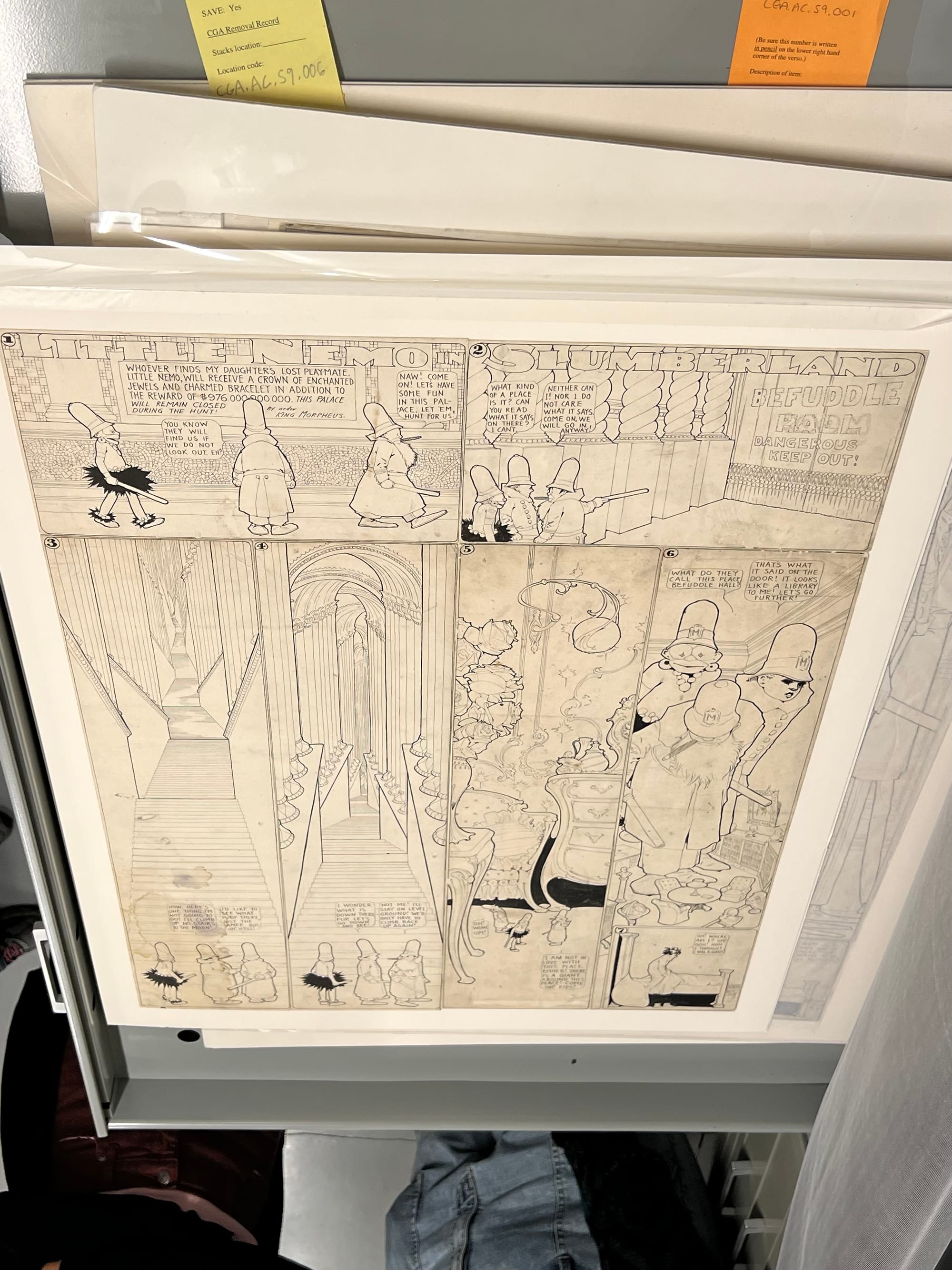

A lot of my influences come from around this time. The visual splendor of a Gilded Age are very appealing to someone with an inclination toward fantasy sensibilities! Nielsen's work on Old Tales from the North overlaps with Winsor McCay's tenure on his comic strip, Little Nemo.

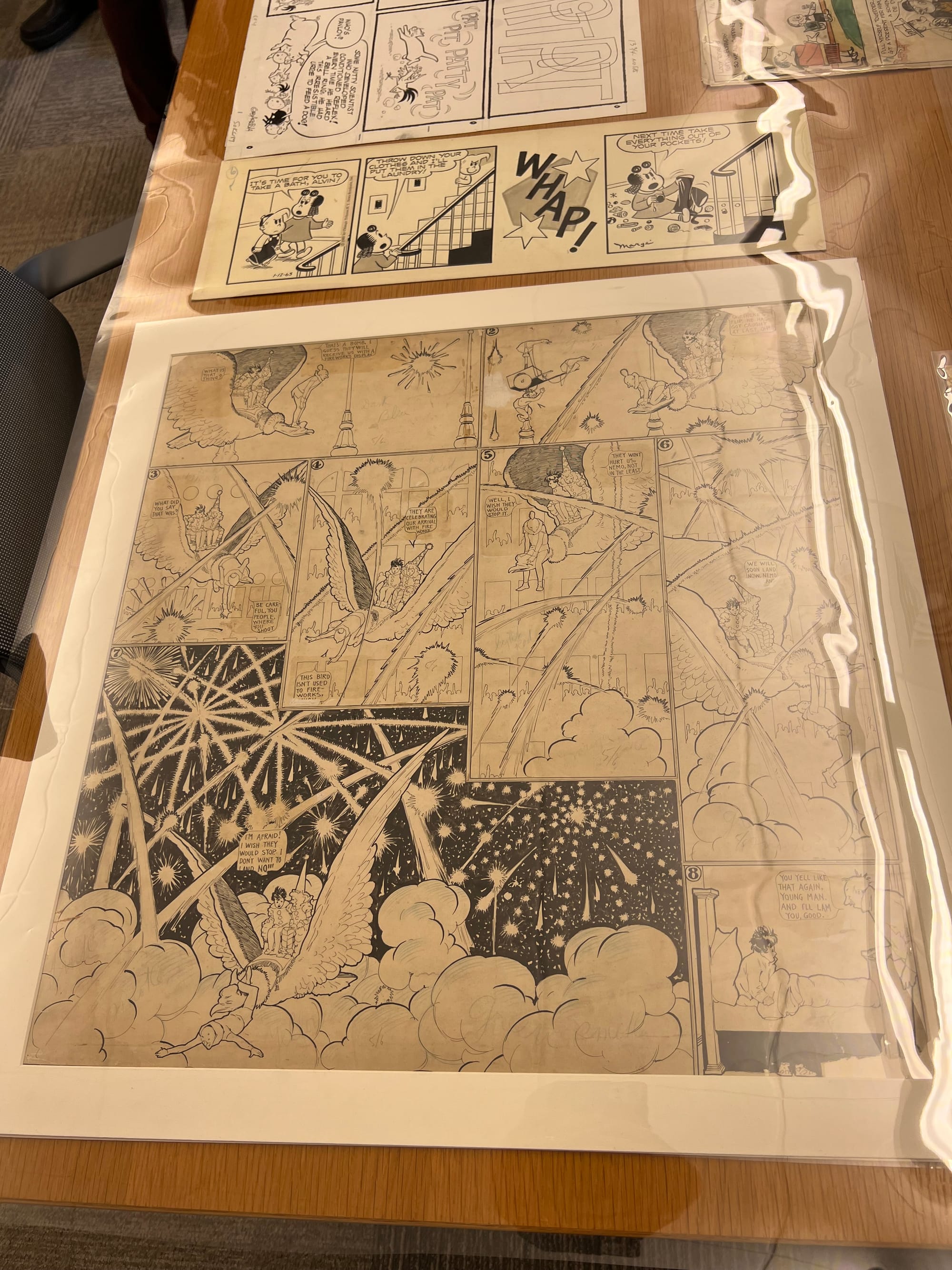

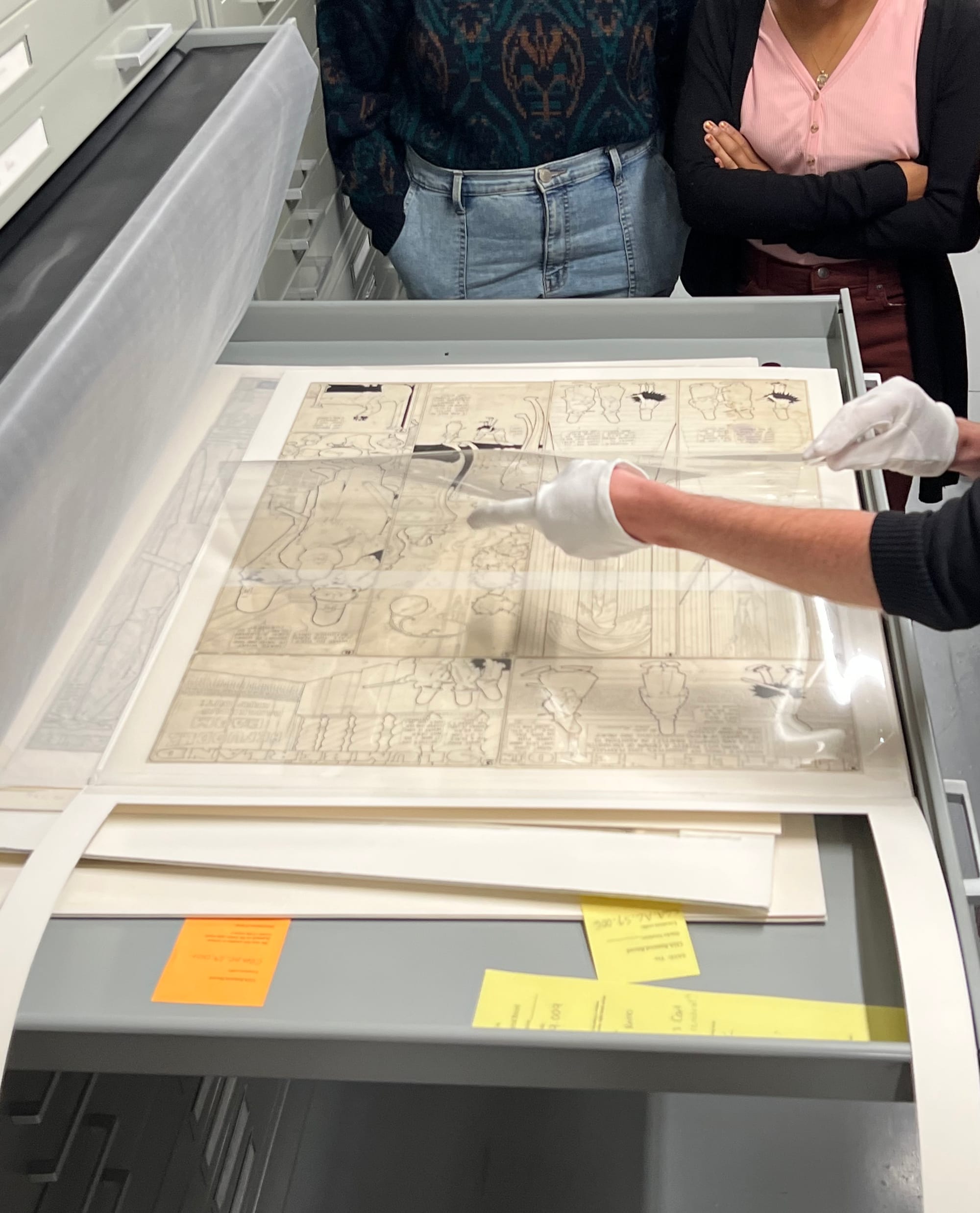

A couple years ago, I had the immense pleasure of seeing some of the original Little Nemo drawings at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University. McCay's drawings are gorgeously realized and, also, intensely racist. As a matter of fact, if you look closely at some of the panels pictured in my phone photos below, you can actually see, nestled between all the beautiful World's Columbian Exposition fin-de-siècle decorative sensibilities, some deeply anti-Black caricatures.

To a great extent, being someone with an interest in commercial forms of visual art from the past typically means that you run into a lot of this. I’m always kind of a little bit dealing with the past, I frequently run face-first into instances of violence embedded into the narrative fabric of the visual world of a time. In subtler instances, I might find that whole swaths of people just never exist in those images. In more overt instances, it helps me trace the lineage of these images as they proceed through the decades, noting the ways they evolve or don't.

Nemo's been on my mind because last week, I had the joy of introducing some loved ones to a movie that has long haunted my childhood. Somewhere in my parents' house is a well-worn VHS tape of the 1992-released animated film Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland. The production on it was apparently bonkers, as outlined in this Nerdist article, with artists, filmmakers, and writers such as Brad Bird, Ray Bradbury, Isao Takahata, Hay Miyazaki, Brian Froud, and Moebius all having had their fingerprints in its process at some point. Production started in the 1980s, the greater part of a century removed from Winsor McCay's time, and so some of the character designs were updated while some, fascinatingly, maintained their aforementioned racist roots.

Roger Ebert noted at the time of the film's release that the visual tropes extended beyond the character, Flip's (pictured above) apparent iconographic lineage stemming from minstrel makeup toward more broadly visually delineating characters with dark palettes as evil. It has a ton of these issues, by today's standards (arguably any day's standards), but I find myself wondering if that's something that needs to be shaken off or if it needs to be frankly depicted and confronted.

There's always this question of acknowledgement versus perpetuation when it comes to visual media, particularly within the auspices of entertainment. In honestly acknowledging the violence and racism in our visual lineages, do we also risk asking our viewers to retread that racial trauma in spaces where the impact of that experience will be asymmetrical across its diverse audience? This framing always slightly ruffles my feathers because it seems to rhyme with a bad-faith premise in argumentative fan spaces—depiction as approval.

Of course, every person is multifaceted, and I've largely landed on the notion that we can't be expected to do everything at once. I think every artist is a steward of their own mode of expression and will become, either by design or by gradual osmosis, acquainted with its complex and oftentimes fraught histories. We become little armchair historians (and I welcome the enthusiasm that comes with it, though the varying degrees of rigor might occasionally present some issues). We wear many hats! For me, one of those hats is being a little too online.

One of my personal red flags in determining whether someone on the internet might be engaging in bad faith is if they seem to believe they can decide which hat I have to wear for their benefit. Sure you're an artist, but why aren't you acting in your capacity as a student of your craft's history right this moment? It presumes I don't know. And sometimes I might not know! But what is the likelihood of that moment evolving into a genuine learning opportunity? Conversely, sometimes people feel the most galvanized when they've just learned about a historical violence for the first time. Didn't you know that Winsor McCay was very racist? Good faith can't be accomplished without some measure of trust, so how would a stranger know that I would treat their sincere treatise with care? And how would I know if a stranger's concern is genuine? A single post can sometimes beget this entire rigmarole!

But I also think this balancing of good faith and unfamiliarity is another hat to wear, and it brings me right back to the top of this post—I'm doing too much. I'm trying to anticipate a problem that cannot ever be one-and-done.

Juggling the thorny histories of all our narratives and all our art is something that requires a great deal of care and an embrace of it as a perpetual challenge with no end in sight. There is no way to one-and-done it. It is entirely Sisyphean. This might sound exhausting and despairing, but I'm optimistic about it. People come fresh to old news every day. There is always someone who will be working all this out for the first time, and that is necessarily messy, but it can also be wonderful.

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland is, weirdly, an adaptation of Bluebeard. Nemo is gifted a magic key that can open every door in Slumberland, but he must never open the door with the key's insignia painted on it. In keeping with the archetypical hills and valleys of that story, Nemo unlocks the forbidden door beneath the idyllic dreamland kingdom and unleashes a Nightmare upon its denizens. Though the movie takes the safest, most unimaginative route—Nemo defeats the Nightmare to return Slumberland to its status quo—it does bear some enough of a resemblance to Bluebeard for it to resonate with idea of the conscientious and curious artist as a steward of their craft, encountering the fraught history of a particular iconography for the very first time. There is always a monster beneath the marzipan palaces.

We might come by it innocently, and even if we didn't put it there, we must take responsibility for it. And I think we can do it. There's no way around this sort of work but to just do it, one bit at a time.